The representation of avatar hands in VR

Whether computer game characters adequately reflect global gamer diversity, isn’t something I’ve given much thought to. But as VR gaming gains traction amongst mainstream audiences, these issues, I imagine, will require much more thought.

For much of my early life, game protagonists were largely presented from a third person’s perspective: either from above or sides; controlling the likes of Mario wasn’t much different from controlling some robot.

Even when first-person shooters like Doom came along, the site of an imposing CRT monitor and a hulking great PC tower was always a clear confirmation of the distance between player and character. Moreover, a pixelated face of an agonised ‘Doomguy’ reinforced this sense of controlling ‘someone else.’

Whether Mario, Doomguy or indeed some blond haired Persian Prince, the skin colour or gender of these characters, wasn’t much of a deal breaker.

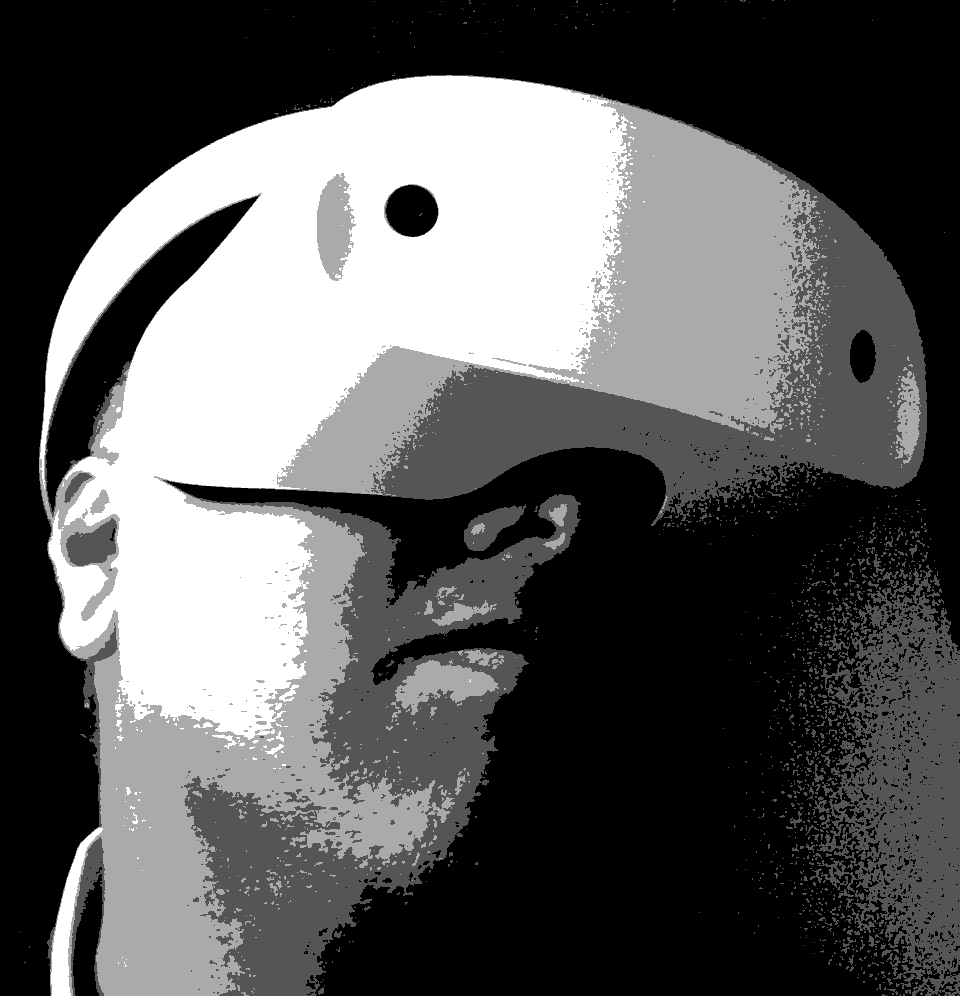

With increasing levels of immersion that’s made possible in modern VR, these issues are being thrust upon us: VR is literally, ‘in our faces.’ So much so that, for example, using simulated hands to bring a virtual burger to our face, users might actively need to resist opening their mouths to take a bite; it’s insane! The form, texture and colour of these simulated hands suddenly become concerns of some importance, therefore.

Users’ experience in VR can be particularly jarring if the appearance of hands fall within, what’s termed, ‘the uncanny valley’: this is when human-like objects aren’t depicted well enough and appear creepy, as a result. Playing host to a body that doesn’t feel like our own can be weird and particularly so when there are vast gender and racial differences to bridge.

VR game designers usually manage to avoid these minefields by either presenting hands in a manner that are stylised and intentionally unrealistic or having them otherwise covered up with gloves and/or other props (guns etc). In this way, the end user also avoids being unduly distracted by their appearance and can focus on the simulated environment and related interactions.

Another approach, used on some occasions, is where users customise the appearance of their Avatar, by changing skin tone, clothing, hair and other features. And that’s cool, but I personally can’t help feeling that the simplest and least distracting approach is to simply leave the hands looking neutral and ‘ghost-like?’

Nevertheless, it’s not a given that users play ‘themselves’ in VR games, rather they might knowingly want to interact as someone else entirely: Batman, for example. Indeed, stepping into someone else’s shoes, ‘embodying’ characters that are so unlike ourselves can be a real hoot! It’s fun blasting hoards of aliens as the ridiculous ‘Serious Sam’ or slashing through future Tokyo as the female ninja assassin in ‘Sairento VR.’ So long as effort is spent on character building (voice-over, cover imagery etc), it can all work rather well. A compelling backstory might also help seal the deal.

Whatever the case, these matters need thinking about; hand interactions are the bread and butter of VR and getting them wrong will leave users feeling neglected and unfulfilled.