The problem with walls

While Architects have, since time immemorial, pushed the limits of what is buildable, their attempts at structural gymnastics ultimately exist within the realms of physical possibility.

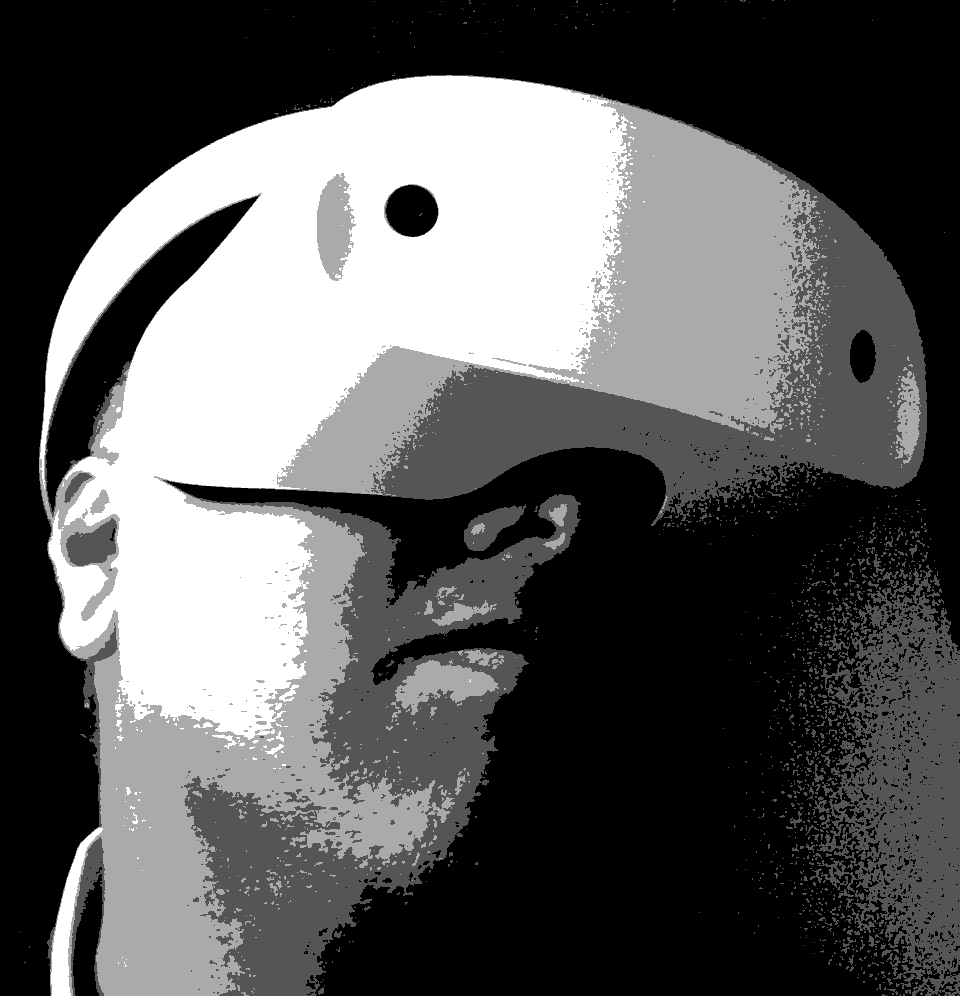

Virtual environments are a different kettle of fish: they aren’t subject to real world forces, for one. To feel sufficiently immersed, however, some measure of realism will increasingly be expected. At the very least, even in highly stylised environments, a sense of scale, proportion and ‘solidity’ should be expressed.

Just how pedantic designers need to be with all this is hard to guage, but getting the balance right will be key to creating virtual spaces that are a pleasure to inhabit.

Without meaning to force traditional architectural theory down VR space designers’ throats, there are important elements from architecture and its long history, absent in contemporary VR experiences, that really should be given greater credence; I’ll discuss some of these below.

Walls as boundary setting elements:

Surely the very first architectural act is that of defining boundaries, without which the potential for space creation doesn’t even exist. These boundaries can range from fuzzy, psychological ones, right through to thick, impenetrable walls; indeed, wall masses are often ‘celebrated’ by architects: gleefully revealing their thicknesses and method of construction for added reassurance and ‘honesty.’

In VR, any connection formed with the simulated environment, any feeling of immersion, immediately breaks down when users can simply pop their heads right into walls and peek through the other side, revealing them to be nothing more than pixel thin! Even much loved VR games (e.g. Robo-Recall) are guilty of this.

This cannot be seen as acceptable; it’s cringeworthy and generally cheapens the experience. A bit like watching a magic trick after already knowing the full details of how it’s achieved: it leads to a dull and lifeless journey.

Standard 2D/3D desktop games don’t have this problem: characters can’t just walk through walls unless it’s intentional and part of the story (e.g. magic potion) or some glitch. This lack of collision is something unique to VR.

No more ‘wall peek:’

Game designers have various solutions to this problem at their disposal, the most common being:-

- As head goes through simulated walls, the screen goes black or blurred.

- Walking through wall results in simulated scene, at the point of impact, moving along with the user. This is how the VR climbing game, ‘Climbey’ handles it.

- As head impacts wall, the player is instantaneously ‘snapped’ back to a point just before the impact; because of how quickly this happens there’s not much scope for nausea. Realising that walls can’t be penetrated, users simply stop trying.

- A combination of ‘1’ and ‘3’; where screen goes black, they’re pushed back to their last valid location and screen quickly fades back in. All this happens within a couple of seconds.

All of these have their pros and cons, but by far the worst solution is to do nothing!

With the 1st solution, users can find themselves becoming ‘lost’ in the ‘dark zone’ behind walls and other so-called barriers; this is highly disconcerting. The 2nd solution can mess up play-space setup and having the entire world moving along with the head seems weird.

On balance, I believe the 3rd and 4th solutions to be the smartest; in fact, from my experience, it’s what most of the post 2017 VR games have gravitated towards. The following are some of games that employ this method:-

- Serious Sam VR series.

- Talos Principle VR.

- Skyrim VR

- DOOM VFR.

- In Death.

- A-Tech Cybernetic.

For an example of this behaviour in Skyrim VR, click the image link below:-

As technology moves on, other solutions will be explored, but I can’t stress enough the importance of proper enforced boundaries; if you don’t have boundaries, you don’t have space in an architectural sense and psychologically you’ll always have one foot in the door and the other foot out, never feeling well immersed and the experience looses its magic.